“Conferring is one of our most potent teaching tactics. It is indispensable when it comes to assessing a child’s understanding.” (Ellen Keene, 2006)

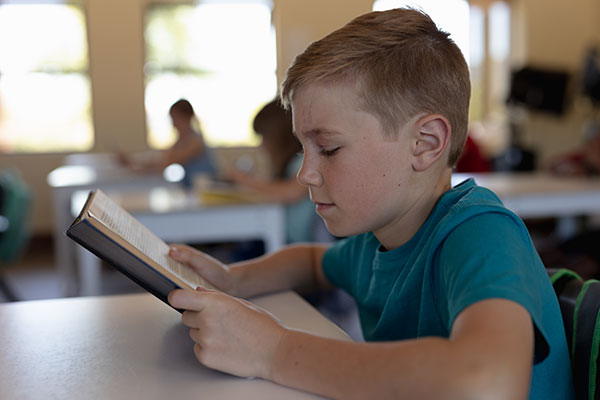

Teachers who confer value the time they spend talking with their students. These rich conversations are a special time where we get to know our students and gather information to make daily, flexible instructional decisions. However, teachers also value conferring as a rich data source. When a teacher confers, they change their stance. They become a fellow reader, but also an observer, assessor and data collector. The teaching purpose of conferring about students’ independent reading is to collect information that helps you plan.

Regular Conferring about Independent Reading has many purposes and goals! Great teachers confer to:

- Gain Knowledge of Students: There is no better way to get to know your students as readers and writers than to confer with them regularly.

- Build a Reading Process: Wise readers develop over time. Conferring provides an opportunity for teachers to mentor students on their development.

- Develop Strategy Knowledge and Application: We value the teaching of reading strategies, so it is important that we spend time fostering the development of reading skills.

- Build Students’ Confidence: Conferring provides students with the opportunity to show teachers what they have learned and how they can apply that learning in the context of their daily reading. Teachers can provide real-time feedback and guidance to celebrate, scaffold and support growth.

- Reflect on Effective Instruction: Teachers can see if their instruction is resulting in students’ learning. Teachers can learn the degree to which students are developing toward mastery in the standards, skills, and strategies they are teaching through real reading and writing experiences.

- Plan Instruction: Data collected from frequent conferring assists teachers in identifying student development in the standards. Data can guide planning for whole group and flexibly grouping for small groups, as well as scaffolding, intervention, enrichment, and extension.

- Set Learning Goals: Setting goals with students at each conference fosters a goal setting, continuous improvement mindset that supports children as lifelong learners.

- Develop Rich Relationships: Taking time to listen and discuss students’ self-selected texts and their reading interest shows that you care about reading enough to devote a regular time to sit with each and every student.

What data do I collect?

Deciding what data to collect depends on your focus for teaching. In a reading classroom, we are developing the six components of reading; oral language development, phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary and comprehension. We are also developing students’ competency in meeting the standards and developing specific reading skills and strategies. In addition, we want to know students’ interest and what motivates them to read.

Teachers can work with grade level colleagues to develop their own method of data collection. You may also use resources and data collection forms from researchers and other teachers. But, the best data is data you will use, so it is important to consider what you need and want to learn from your students.

A simple way to begin data collection during conferring is to schedule the first five sessions around these goals:

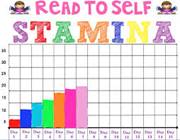

- Reading Level Range, Interest and Engagement – Talk to students about their independent and instruction reading levels. Share a few examples of texts within their range. Discuss how to choose texts that fall within their range.

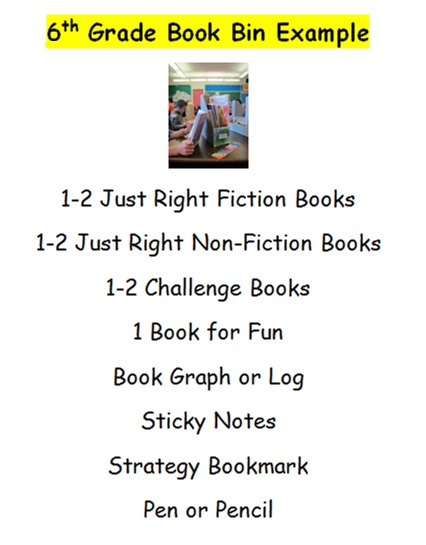

- Good Fit Books – After teaching several mini lessons about selecting good fit books, confer with each student to ensure that they can self-select texts within their range.

- Book Bin – In Blog #&, we talked about develop a Book Bin process or protocol in your classroom. Meet with each student to talk about what is in his or her Book Bin. Review the class protocol together.

- Focused Strategy of the Week – Most reading lessons have a learning target or goal for focusing on a reading skill or strategy. Meet with each student and ask how that skill or strategy is used while reading.

- General Fluency AND Comprehension – Sit with a child and ask them to read a segment of the texts they are currently reading. Do a mini running record, recording the possible miscues. Note their fluency. Ask one or two comprehension questions about the section they read. Discuss their understanding of the text so far.

After you have met five or six times with each student in your classroom, you will begin to identify the elements you wish to collect data about while conferring. Discuss what you are learning with your colleagues or grade level team and create a conferring format as a group. Meet every week or two to talk about the data and make revisions in your process.

Developing your method and use of data from conferring takes time, but it is worthwhile. The data you collect from conferring with students, combined with other anecdotal data and student work products, can give you ongoing knowledge of each student as well as your classroom as a whole.

RESOURCES

Allen, P. (2012). Conferring: The Keystone of Reader’s Workshop. New York, NY: Stenhouse.

Boushey, G., & Moser, J. The cafe book: Engaging all students in daily literacy assessment and instruction. New York, NY: Stenhouse.

Keene, E. (2006). Assessing Comprehension Thinking Strategies. Huntington Beach, CA: Shell Education.

Kleine, R. (2015) Rick’s Reading Workshop: Silent Reading. The Teaching Channel. Click to retrieve.

Miller, D. & Moss, B. (2013). No More Independent Reading Without Support (Not This But That). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Serravallo, J. & Goldberg, G. (2007). Conferring with readers: Supporting each student’s growth and independence. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

This article is #12 in the twelve-part series, “Getting My Classroom Ready for Balanced Literacy Instruction: Classroom Culture and Environment.”